Sameer Arshad Khatlani

When Sheikh Abdullah and his wife, Wahid Jahan, resolved to empower women by educating them in Aligarh, a dusty town in northern India, they knew how daunting the task would be. Hindus and Muslims both opposed the idea, fearing Western education, which was first introduced in far-off British-ruled coastal centers, would lead to ‘immorality’.

But the couple persisted and started Aligarh Girls School defying all odds. The school went from strength to strength and would in 1937 be upgraded to Aligarh Muslim University (AMU) Women’s College when the literacy rate among India’s women was just three percent. The college came into being almost two decades before New Delhi’s premier Lady Shri Ram College was founded.

Years later, Abdullah spoke with a sense of triumph and pride about their labour of love and realisation of their dream in the form of the college. Addressing a gathering of the students of the college, he said education had the same bright effect on them as silver polish has on pots and pans when they came out of the darkness after innumerable odds. He underlined that educated girls illuminated their society.

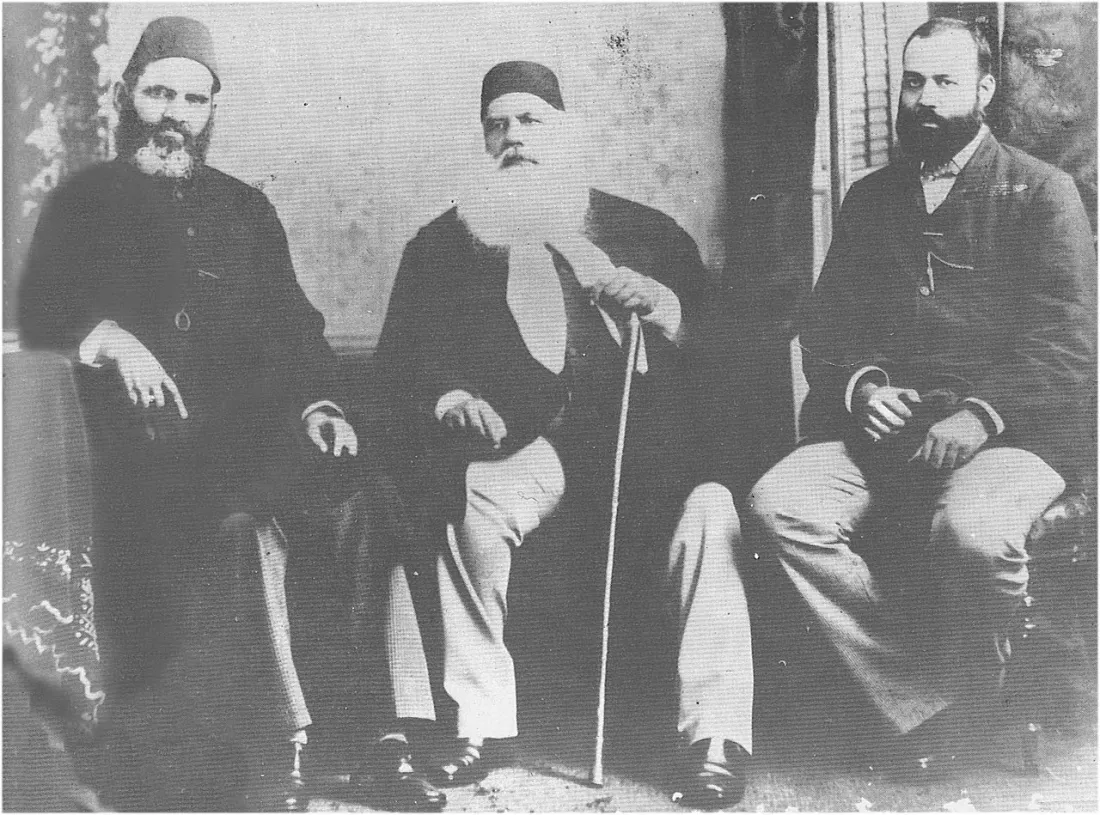

The couple was part of AMU founder Sir Syed Ahmad Khan’s Aligarh Movement for modern Western–style education based on a rational outlook and opposition to blind adherence to tradition. Educating women became their lifelong endeavour. The Muslim Educational Conference, a platform for mobilising masses to promote education, formed a department for promoting women’s education in 1898. The idea was also promoted through the Aligarh Institute Gazette.

In December 1902, Abdullah, who was among Sir Syed’s close associates, was made in charge of the women’s educational project, and a special ‘Aligarh Monthly’ issue was published the following year for the purpose. Educated at AMU, Abdullah, who was born in Poonch in Jammu and Kashmir, started the journal ‘Khatoon (woman)’ for the promotion of women’s education in 1904 and founded the Female Education Association the same year to promote his cause and provide support to institutions working for it.

Bhopal’s ruler, Begum Sultan Jahan, provided a shot in the arm for the project when she offered Abdullah a grant for the Aligarh Girls School to take off with five students and a teacher on October 19, 1906. Science and social science were part of the first syllabus, making Abdullah among the pioneers of female education in India. Abdullah was duly awarded Padma Bhushan, India’s third-highest civilian, in 1964 in recognition of his contribution, which puts him in the league of the founders of India’s first women’s college, Calcutta’s Bethune College (1879) and Lucknow’s Isabella Thoburn College (1886).

Aligarh Girls School was also the first for Muslim girls in north India. Abdullah’s daughter, Rashid Jahan, was among the students who honed their rebellious streak there. Rashid Jahan chose a radical path as a communist and a rebel. Her personal life and the literature she produced were ahead of her time. A gynecologist, who was among the first Muslim women to study medicine at Lady Hardinge Medical College in Delhi, she spotted a khaddar sari with a sleeveless blouse and short hair. She would travel to far-off places to treat the poor.

Rashid Jahan’s lifestyle and ideas were rare for women of her generation in the first half of the 20th century. She attacked female seclusion, patriarchy, and misogyny and wrote about bodies with the exactness that only a doctor with knowledge of human anatomy would. She influenced iconic Urdu poet Faiz Ahmed Faiz with Marxist ideas. Her husband Mahmuduzzafar was Amritsar’s Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College principal while Faiz taught English there.

Rashid Jahan was one of the authors of a polemical collection of stories ‘Angaarey (embers)’ which triggered outrage in the 1930s with its attack on British colonialism and religious conservatism. ‘Angaarey‘ was banned in March 1933 but would lead to the formation of the Progressive Writers’ Association. The association revolutionised Urdu literature and attracted people such as poets Kaifi Azmi, Ali Sardar Jafri, and iconic Urdu writer Ismat Chughtai.

Rashid Jahan would inspire Indian and Pakistani feminist Urdu writers to explore forbidden subjects such as sex. Chughtai was Jahan’s junior at the Aligarh school. Her ‘Lihaaf (quilt)’, which humorously dealt with lesbianism and the sexual desires of women, also triggered a storm and prompted British colonialists to charge Chughtai with pornography. ‘Lihaaf’ portrayed alternative sex in 1941 two decades before second-wave feminism. Her portrayal of a woman’s conditioning vis-à-vis her body had no parallels in the West.

The feminist subversion of patriarchy by Chughtai, who went on to become South Asia’s top feminist after literary grounding at the Aligarh school, with ‘Lihaaf’ predated Simone De Beauvoir’s ‘The Second Sex’ by five years. Her work draws as much attention as her Western peers in almost every department where South Asian Studies, Women’s Studies, Feminist/Gender Studies, and South Asian literature are taught, according to Chughtai’s translator Tahira Naqvi.

Naqvi believes Pakistani poets like Kishwar Naheed and Fehmida Riaz derived inspiration from Chughtai’s bold and uninhibited writing style. Described as one of Urdu fiction’s pillars, Chughtai also influenced the likes of writer Hajra Masroor and novelist Bano Qudsia.

(Sameer Arshad Khatlani is a journalist and the author of The Other Side of the Divide) Source: https://mypluralist.com